Source: Prepared based on Meister (1999)

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Visión de futuro

REVISTA CIENTIFICA

ISSN 1668 - 8708 VERSION EN LINEA

URL DE LA REVISTA: http://visiondefuturo.fce.unam.edu.ar/index.php/visiondefuturo/index

E-mail: revistacientifica@fce.unam.edu.ar

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

AÑO 17, VOLUMEN 24 N° 1, ENERO - JUNIO 2020

URL DEL DOCUMENTO: http://visiondefuturo.fce.unam.edu.ar/index.php/visiondefuturo/issue/view/17

Los trabajos publicados en esta revista están bajo la licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 2.5 Argentina

THE LEARNING COMMUNITIES IN THE ORGANIZATIONS

Manuel Alfonso Garzón Castrillon

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The learning communities in the organizations

(*) Manuel Alfonso Garzón Castrillon

(*) FIDEE Research Group

Foundation for Business Education Research and Development

Barranquilla, Colombia, South America

manuelalfonsogarzon@fidee.org

Reception Date: 06/06/2018 - Approval Date: 05/06/2019

ABSTRACT

In this article the purpose is to make a conceptual review of the background, the definitions, with which a proposal of a definition is reached, the classification of learning communities, the goals and principles of the learning communities, the characteristics of the learning communities, virtual learning communities and Physical Learning Communities (PLC); Virtual learning communities (VLC); Organizational learning and finally we made some conclusions.

KEYWORDS: Learning Communities (LC), Physical Learning Communities (PLC); Virtual Learning Communities (VLC); Organizational Learning (OL).

INTRODUCTION

The stimulus for today's high interest in learning communities comes from many sources, which often have different motivations that, however, complement and reinforce each other. Most people are interested in learning communities because they offer the hope of making the university a more comprehensive and comprehensive learning experience for students. But learning communities can range from unstructured programs that offer people the opportunity to take a set of courses in common, highly structured programs of integrated courses are taught in team teachers from different disciplines.

Taking into account that the knowledge produced by organizational learning must be communicable, consensual and integrated into the organization by itself. That is, the organization must institutionalize the process by creating steps and learning systems whose main task is to provide information to directors and managers. This fashion perhaps was imposed by the Japanese as established by Medina et al. (1996), with the instrumentation of the planned obsolescence of the product. Casio is a clear example.

For its part, Palacios (2000) states that the Western model (rationalism), the humanist current of the administration, when combined with the general theory of systems and the theory of information, led to the development of a theory of organizational learning, which It was first formulated by Senge (2002) in the fifth discipline. According to this author, the first thing to recognize and identify the intelligent organization, are the seven obstacles to learning and design an organizational strategy to develop

Learning communities are a commitment to a model that belongs to the information society, and that, in addition, allows us to overcome the social, economic and educational inequalities in which it is generated. Learning communities are raised as a response from knowledge management, where transforming an organization is much more than transforming it into itself, it is transforming its internal structure and relations with its immediate environment at the same time.

The five disciplines of organizational learning proposed by Senge (1990): systemic thinking, personal mastery, mental models, building a shared vision and team learning, show that it has already been seen that sharing knowledge requires materializing it. This gives rise, in every organization, to a stock of materializations of knowledge, which makes it available to all its inhabitants. This common or collective knowledge cellar, (almost always archived in digital format), has particular properties, which we must examine with some care to differentiate them from individual knowledge databases (very often stored in neuronal form).

On the other hand, Muñoz-Seca et al. (2003) proposes that, to understand the role of collective knowledge, the operation of a logical agent will be considered, and to use these agents in the analysis of the relationships between the inhabitants of an organization.

In this article the purpose is to make a conceptual review of the background, the definitions, with which a proposal for a definition, the classification of learning communities, the goals and principles of the learning communities, the characteristics of the We are learning communities and finally we make some conclusions.

DEVELOPMENT

Method

To carry out this review, the methodology used required the development of four stages, the first was the literature search; the second stage was the organization of data; the third was the content analysis and the fourth was the writing. For this process, eighty-four (84) documents were placed on secondary sources database of scientific articles such as Scopus, WoS, and Scielo, and the type of review is qualitative, descriptive.

Antecedents

The philosophy that underlies learning communities is most commonly attributed to Dewey in the 1920s and his recognition of the importance of the social nature of all human learning (see, for example, Brown and Duguid, 2000; Solomon, 1993; Smith, 2003). Other writers suggest that similar philosophies have existed in one form or another since at the least the first century AD (Lenning and Ebbers, 1999), or much earlier than this, at the time of Plato (Longworth, 2002). At the end of the 20th century, although the learning communities were not well understood or well defined, they were among the most discussed concepts in higher education circles (Kezar, 1999, p. Ix). This discussion continues today, with the definition of learning communities that continue to evolve in response to the diverse needs of the people and communities in which they work.

The emergence of learning communities can also be the result of self-organization, as explained by Jean-Paul Sartre (1976) according to Raynova (2002), initially, members could compose an informal grouping and share a common place in time and in space, physically or electronically.

Tinto and Russo (1994) presented coordinated study programs. Tinto expanded his study in this area by developing a project on Learning Communities in 1998, and Cross (1998) also contributed by writing Why learning communities? Why now?

The main purpose of the learning communities is to maintain control and cooperation among the members of the organization and allow it to continue with its present actions and activities in order to achieve its objectives. Learning communities will allow collaborators to detect and correct any errors. On the above, Gareth Morgan (1980, 1998) has examined the way in which metaphors are at the foundation of our ideas and explanations about organizations.

There have been attempts to examine the role of metaphors and show their importance in bibliography, philosophy and language. The above shows that a learning community is not a commission where each member acts only on behalf of their area, but a working group capable of learning and acting beyond their initial mandates. In this team, says Gore (1998), there should be no prescribed roles or standardized functions, but the leadership could be rotating with the different phases that the program was going through.

Peter Senge (1990) published his reference book, The Fifth Discipline, on the creation of learning organizations in the corporate world, researchers and education professionals examined how to reconceptualize schools as professional learning communities (PLCs).

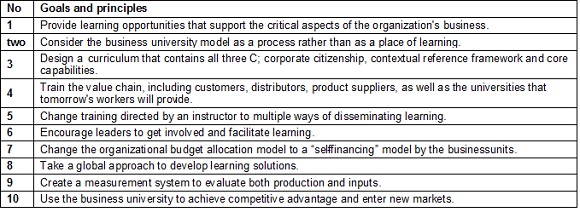

World-class learning solutions, says Meister (1999), are the result of forming collaborative partnerships with a large number of innovative organizations. With a view to establishing a truly market-oriented education system, organizational universities must form alliances with a large number of partners in the education sector, including local universities, universities of national and international reputation, community institutions of higher education, technical institutes, training companies, consulting organizations and for-profit education organizations that offer accredited e-learning courses. Learning communities must establish the following goals and principles: Meister (1999).

The increase in the popularity of this vision of learning communities for Yarnit (2000) in the United Kingdom was a response to global change in the late 1980s, which included: global economic change; the advent of the knowledge economy; and the wide availability of information and communications technology (ICTs). These changes had a profound impact on urban communities, which they faced: the prospect of rising unemployment, due to non-competitiveness in a global economy; government spending cuts; population pressures in urban areas due to demands for employment and housing, and emigration from developing and excommunist countries; and a destabilized political arena (Yarnit, 2000).

Finally, it is required to foster the emergence of learning communities in which autonomous work units generate an environment that must tend to encourage autonomy and taking responsibilities of each in the results (vision of individual power as multiplier the effects of the interventions). Ideas storm camps are a mechanism with which individuals seek the harmony of being involved in both bodily and mental experiences (Nonaka et al. 1999).

Definitions

First, we will address the term community based on Riel and Polin (2004), as a group of multigenerational people, at work or in the game, whose identities are largely defined by the roles they play and relationships that share in that sense, group activity. The community derives its cohesion from the joint construction of a culture of daily life based on behavioral norms, routines and rules, and a sense of sharing purposes. Community activity also precipitates shared gadgets and ideas that support the group.

A community affirms Riel and Polin, (2004), can be multigenerational; that is, they may exist throughout the time and lives of individuals. In short, a community differs from a mere collection of people because of the strength and depth of the culture that it is capable of establishing and which in turn supports the activity and cohesion of the group.

In this way the sense of community is the feeling that the members have a membership, the members are important to each other and to the group and a shared faith that the members' needs will be met through their commitment to be together.

The term community has quickly become a cliché of jargon used to refer to a social group in which learning is an explicit, intentional objective. Understand the functional. The meaning of learning communities, therefore, we must anchor our definition of the term community, regardless of structure, learning communities have in common three important elements: Riel and Polin, (2004).

They provide an active learning environment.

They build community, both academic and social.

They connect the study of theory with applications.

The term learning communities is used in various ways within the literature, often without an explicit definition. Two main uses can be discerned; The first focuses on the human element of communities, and the benefits that accrue from the synergy of people in ordinary places or common interests as they work to share understandings, skills and knowledge sharing purposes; the second focuses on curricular structures (that is, an inanimate structure) as a means to develop a deeper learning of predetermined (implicit) curricular content.

It is based on a broad body of theory related to Education, Administration, Psychology and Sociology. Learning communities are recommended in an increasingly complex world where we cannot expect a single person to have sufficient knowledge and skills to face the complexities of organizations, our society and the individuals and tasks to which they are face. They are consistent with a constructivist approach to learning that recognizes the key importance of interactions with others and the role of social interactions in the construction of values and identity.

The Senge (1990, p. 3.) Defined as "organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns nurture of thought, where are collected aspiration is free, and where people continually learn to learn together."

They are often subdivisions of larger organizations, or activities or systems. While they may be short in duration or more durable, they support the work of ongoing groups to improve their understanding and develop their ability to work creatively, in a system of overlapping circles, In the common nucleus, where the three overlap, is the fertile ground of organizational learning (Senge, 1990).

They are characterized by face-to-face interaction, and gradually and their members end up knowing more about their personality, fields of interest and possible purposes of each other, as well as the corresponding forms of behavior acceptable or not for the rest of the group (Schutz, 1962; Wenger, 1998).

If we stop at the evolution of learning communities, they can be formed from outside, for example, Von Krogh and Ross proposes. (1994), a department head, a research and development manager or an engineer responsible for product development. In this case, the task of the community, belonging to it, the benefits of such membership and the distinction are based on organizational initiatives, so that the community operates as a team.

The wider and more inclusive use allows describing situations in which a series of groups and institutions have joined forces to promote systematic social change and share (or jointly possess) the “risks, responsibilities, resources and rewards” (Himmelmann, 1994, p. 28). In geographically linked examples, allies often include educational institutions, government agencies, industry partners and community groups. It is a phenomenon of partnership between public, private and nonprofit organizations to increase the capacity of the community to set up and manage their own future is said to be a "collaborative empowerment" (Himmelmann, 1994, p. 27).

Defines very briefly Cross (1998) as groups of people involved in intellectual interaction with the purpose of learning, to which some questions arise: Why is there so much interest in learning in communities?, the reasons can be divided in three broad categories: philosophical (because learning communities adapt to a changing philosophy of knowledge); based on research (because learning communities conform to what research tells us about learning) and; pragmatic (because learning communities work).

Most radical, for Cross (1998) is that the most coherent concept is based on the concept of collaborative learning, as Whipple (1987) argues, the strengths of social construction for learning communities are several: social construction conceives the knowledge not as something that is transferred in an authoritarian structure but rather as something to work interdependently to develop thus, active learning about passive learning, cooperation on competition and promotes community about isolation.

The concept has been used to describe a cohesive community as one that incorporates a learning culture in which everyone participates in a collective effort of understanding (Bielaczyc & Collins, 1999, p.271; Collins, 1998).

They facilitate the exchange of knowledge, and also have the potential to create new knowledge that can be used for the benefit of the community as a whole and / or its individual members. This overview contrasts with the use of learning communities as enhancers of individuals' learning, generally in educational settings. However, even when applied in a narrower sense to individual institutions, it is recognized that "[building] communities of learners creates an environment that can potentially advance an organization and an entire society" (Lenning and Ebbers, 1999).

They are life in the community itself, in the words of Nonaka et al. (1999) a concept that is generically associated with the tribal lifestyle where one generation transmits its cultural heritage and ideology to the next generation. The scheme is simple: the training of the youngest is a system to prepare human resources as the community needs them to guarantee their perpetuation.

A learning community addresses the learning needs of your locality through the association. It uses the strengths of social and institutional relationships to cause cultural changes in perceptions of the value of learning. Learning communities explicitly use learning as a way to promote social cohesion, regeneration and economic development that involves all parts of the community. (Yarnit, 2000, p. 11).

European literature emphasizes the learning of cities, learning cities and learning regions, in Australia according to Keating, Badenhorst & Szlachetko, (2002) the notion of learning communities prevails. However, while European definitions tend to identify geographic location as an element that links learning communities, Australian definitions tend to define that learning communities apply to communities of common interest, as well as geography.

These “are developed where groups of people, linked geographically or by shared interests, collaborate and work in partnership to address the learning needs of their members. Learning communities facilitated through adult education and the community are a powerful tool for social cohesion, community capacity development and social, cultural and economic development.” (Department of Education, 2003, p. 12).

They are characterized as "a project of social and cultural transformation of an organization and its environment, to achieve an information society for all people, based on dialogical learning through participatory community education as embodied in all their spaces. " (Valls, 2003, p. 8).

They are also conceived as “an organized human community that builds and engages in its own educational and cultural project, to educate itself, its children, youth and adults, within the framework of an endogenous, cooperative and solidarity effort, based on a diagnosis not only of their deficiencies, but, above all, of their strengths to overcome such weaknesses ”(Torres, 2004, p. 1).

After this review it can be concluded that there is no universal definition of learning communities therefore may have nuances of interpretation in different contexts, but it seems to be a broad international consensus which suggested that learning communities for this article , based on Astuto, Clark, Read, McGree and Fernández, (1993); Gold (1994); Medina et al (1996); Hord (1997); Gore (1998); Meister (1999); Nonaka et al. (1999); Palaces (2000); Krogh et al (2001); King & Newmann, (2001); Peluffo et al (2002); Mitchell & Sackney, 2000; Toole & Louis, 2002) Muñoz-Seca et al (2003); Quintero et al (2003): They are a group of people organized to share and critically interrogate their practice in a continuous, reflective, collaborative, inclusive, learning-oriented manner and that promotes growth, operating as a collective organization, are autonomous units that generate an environment that should tend to stimulate the autonomy and the taking of responsibilities of each one in the results. It is a team capable of learning and acting beyond the initial mandates.

They allow to conserve knowledge networks

Allows the formation of the relay generation

They are self-organized.

They can be virtual,

They allow to share tacit knowledge, through socialization

They are not delimited by group, departmental or divisional boundaries

Communities can be formed thanks to narrative skills.

The identification of knowledge units must be understood as the virtual groups of a knowledge organization. This is in the words of Muñoz-Seca et al. (2003), an organizational unit that contains the knowledge of a competition. Therefore, from the diagnosis of competencies of the organization we can obtain the knowledge units.

As can be inferred, a learning community allows a person to belong to a set of learning units, depending on their knowledge profile. The virtual and polymorphic nature of the knowledge unit makes this multiple membership possible without complications. Sharing such images by the members of the organization, and the implicit norms and assumptions that this entails, is called the theory in use of the organization (Argyris and Schón, 2009).

Therefore, there are common themes that link definitions and uses. These include: common or shared purpose, interests or geography; collaboration, partnership and learning; respecting diversity; potentiating and improving the results.

Classification of learning communities

Learning communities have been classified into three, task-based learning communities, practice-based learning communities and knowledge-based learning communities, which are described below.

Task based learning communities

The first distinction of possible learning communities that can be promoted in organizations is for Riel and Polin, (2004), those based on tasks. These are groups of people, organized around a task that works intensively together for a specific period of time to produce a product. While the specific group may, in the strictest sense and not share all the properties of a community that we list in our definition of community (eg, generational handled in a very different way), people involved in them often experience a strong sense of identification with your partners, the task and the organization that supports them In task-based learning communities, the emphasis is on learning.

Task-based learning communities are used to indicate a form of learning that is very different from simple collaboration (Schrage, 1995).

The explicit objective of task-based learning communities according to Riel; and Polin, (2004) is to gather a group of people with the maximum diversity of perspectives that can focus on common issues or problems, and then, through the processes of group formation, discourse and common work.

Learning communities based on practice

A community based on practice arises following Riel and Polin, (2004), around a profession, discipline or field of effort. It can be as broad as a group of Linux programmers worldwide, developing and sharing their work in online magazines, conferences and forums. Or it can be as narrow as a team of teachers who work together to improve practice on the site by meeting, discussing, sharing, around their practices with new methods and materials. It differs from a learning community based on tasks significantly, most of which are captured by voluntary participation in the field or practice.

There is a strong emphasis on the notion of a community as a shared activity and objectives, although it establishes Riel and Polin, (2004), that there may be differences in the experience and scope of their participation in practice. In addition, members share a social responsibility to learn and learn for the community.

The knowledge-based learning communities

Knowledge-based learning communities build, use, rebuild and reuse knowledge in deliberate and continuous cycles (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 1994; Bereiter, 2004; Hewitt (2009), a knowledge building community seeks to advance the collective. Knowledge in a topic or field of research, and do so in a way that supports the growth of each individual in the community, that is, the intentional development of experts within the community. The group is involved in a process of thinking about the knowledge as knowledge Members of the knowledge-based learning community continue to adapt the product of knowledge to new and emerging conditions, to better understand processes that are dynamic in nature.

The clearest example proposed by Riel and Polin (2004), a community of knowledge construction is a group of researchers working to understand a phenomenon, concept or relationship, such as earthquakes, black holes or the effect of the divorce in children. Like most learning community, these groups are presented within programs, organizations and professional societies and work to make the knowledge of the program, the organization or the community an externalized object of tacit understandings, unbundled practice and available for iterative evolution and in organizational life.

Goals and principles of learning communities

The main objective of a learning community is to learn with the support of a leader, teacher or teacher. The interdisciplinary objective is to increase individual and collective knowledge. This requires a deep understanding of the objectives. Another additional objective is to increase the capacity for communication and cooperation, as well as the capacity to assume one's own responsibility.

The goals and principles of the learning communities are listed in Table 1,

Table 1. Goals and principles of learning communities

Source: Prepared based on Meister (1999)

The strategy of Business University or Corporate University as a learning community is the effort made by the organization to foster the same spirit of lifelong learning that we find in an exceptional university. William Esrey, quoted by Meister (1999) president of the Sprint board, summarizes the goal of this model when he says: Sprint University of Excellence is more than just a place or even an educational system. Rather, it is a living being composed of instructors, apprentices and curriculum designers.

Learning communities contribute according to Ongaro, and van Thiel. (2018) to the generation of four types of preeminent learning: epistemic learning; reflexive learning; learn through negotiation; and hierarchical learning. These four are distinguished by the ways in which participants develop these capacities in each one:

1. Epystemic, where participants work in environments marked by a clear and complex experience of problems. Ongaro, and van Thiel (2018).

2. Reflective: when the problems are complex but the knowledge is objected, the experience is uneven and extends to the whole society. Ongaro, and van Thiel (2018).

3. The result of the negotiation, where capacity development is eminently political. The opposite pole of the epistemic mode, where an attitude of truth search prevails. Instead, in the negotiation mode, they work with a small range of interest groups to develop a capacity that meets agreed political preferences, based on consensus and power, not policies based on truth and evidence. Ongaro, and van Thiel (2018).

4. Hierarchically, where capacity development is limited and shaped by powerful forces such as courts, binding norms or political principles. Learning for capacity development takes here two opposite ways: the acceptance and learning the rules that mediate the action and, more radically, the resistance sees capacity development as the function of an escape from the broader institutional context. Ongaro, and van Thiel. (2018).

In complex organizations, such as the current ones, individual learning is combined with team learning, organizational and inter-organizational learning. For these purposes, it is useful to think of the four modes as organizational learning modes related in the preceding paragraphs, rather than individual modes.

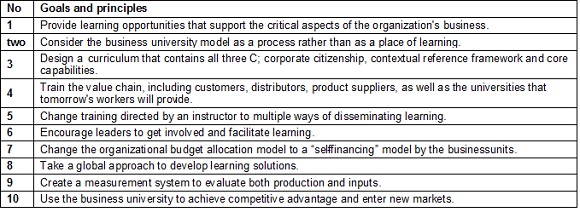

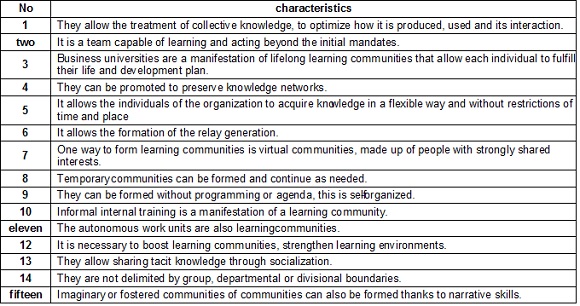

Characteristics of learning communities

From the bibliographic review carried out in relation to learning communities as a condition for organizational learning, an approach is made to its characterization. In table 2:

Table 2. Characteristics of learning communities

Source : Prepared by Garzón (2005) based on Gold (1994); Medina et al. (1996); Gore (1998); Meister (1999); Nonaka and Takehuchi (1999); Palaces (2000); Von Krogh and Ross (1994); Peluffo et al. (2002); Muñoz-Seca et al. (2003); Quintero et al. (2003)

Virtual learning communities

One way to form learning communities is through virtual communities, made up of people with strongly shared interests, as Nonaka and Takeuchi (1999) affirm, a natural action site to share knowledge and develop skills.

It is clear according to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1999) that members must have very strong reasons to participate in such online communities, thus the most vibrant lasting online communities are those that bring together people with a deep personal interest in the existence of that community. Along the same lines, Nonaka and Takeuchi (1999) point out that there are two types of communities that are interesting to explore to facilitate learning:

• The temporary built around the substantive theme of a training course.

• The continuous ones that work supporting the achievement of continuous or long-term learning objectives.

Virtual learning communities can be defined as networks of social relationships in which interaction are critical factors. (Lock, 2002), all members of the group are learners, and the group is organized to learn as a complete system, supported by information technology and communication (ICT), for which it requires facilities such as discussion forums, fundamental to the process of establishing electronic learning communities.

Virtual communities for Daniel et.al. (2003) take several forms, most of which are organized around models of temporary communities. They share certain elements, such as common objectives, shared understanding, trust and adherence to a common set of social protocols. Our interest in social capital focuses on the role that learning plays in virtual learning environments.

The virtualization of learning communities provides opportunities that do not exist in the Physical Learning Communities (CAF). The virtual learning communities (CVA) provide the ability to identify who is involved in a process. It is also possible to audit the behavior of each participant, either by their words (dialogues), or by their actions on artifacts (Avouris et al. 2003). Virtual traces help us to know the history of the community (Overby 2008, 2012).

Various types of communities develop throughout the world. Learning communities are a type of popular community. In learning communities, members communicate to meet their educational needs. They set goals, select methods and collaborate to achieve them. A learning community is not just a group that learns in collaboration. Building a community takes a lot of time. Its members have a common history, beliefs, values and trust (Hiltz 1985; McMillan and Chavis 1986; Preece and Maloney-Krichmar 2003; Rheingold 1993; Rovai 2002). Social interactions between participants and communication with their peers improve their sense of community (Dawson 2006).

This sense of community is very important as it is negatively associated with crime and victimization (Battistich and Hom 1997. The structure of the best-known learning community is the physical classroom (Scardamalia and Bereiter 1994).

In recent years, like many other activities, the Physical Learning Communities (PLC) have been transformed into virtual communities, such as Virtual Learning Communities (VLC) (Boughzala et al. 2010). A variety of web tools and technologies has led to the establishment of online learning communities (Tan and Lee 2018). The actions of community members and the interactions between them support learning and lead to deeper understanding (Overby 2008).

It also helps them transform their roles and, consequently, their behavior (Rovai 2002). Web-based collaborative learning environments facilitate interaction between participants and support the learning process (Barana et al. 2017; García-García et al. 2017; Jeong et al. 2017; Ng. 2017). The sense of community is not facto in virtual learning communities. The design of a program and andragogy are the critical factors, while the medium is not. Therefore, it is essential that they emphasize the construction of the sense of community. The dialogue between the members supports the construction of the community (Rovai 2002). Members of virtual learning communities (CVA) can transform their roles and feel satisfied through their participation.

The sense of community also exists in virtual learning communities (McInnerney and Roberts 2004). Its members create links, feel members, influence each other to create norms, share common values and trust each other (Koh and Kim 2003). They experience this sense of community primarily through their dialogues (Blanchard and Markus 2004; McInnerney and Roberts 2004). Combined or hybrid learning (offline activities in physical communities, extended in the virtual environment) produces a stronger sense of community than traditional or online courses (Fan et al. 2012; Overby 2008; Rovai and Jordan 2004). The language used in virtual learning communities (CVA) provides a common symbol system, which is a basic element for a community (McMillan and Chavis 1986).

Virtual learning communities offer many advantages to their members: participation (regardless of distance or time) and the ability to participate even for people with disabilities (Overby 2008). On the other hand, the virtual essence poses challenges such as aggressive behavior and cyberbullying that may arise.

Virtual learning communities for Nikiforos et.al. (2018) is de facto democratic, since the rules are not imposed from the outside, but are built internally, within the community, with the participation of all its members, which leads to the creation of the community culture. Fear seems to be the reason that results in the silence of aggressive members, thus confronting the internal discourse of the community.

This is an interesting finding, from Nikiforos et.al. (2018) who propose a framework to modify aggressive behavior in a more permanent way: creating virtual learning communities is a procedure that motivates its members to behave according to the rules of the community, thus modifying their primitive motivation.

In a web context, similar results were supported by Bers et al. (2010), which demonstrate the viability and security of a virtual community as a possible psychosocial intervention for adolescents. In addition, Buchanan and Coulson (2007) represent that online support groups can represent a convenient and beneficial tool that can help certain people cope with their anxiety / phobia and successfully receive medical attention.

In general terms, virtual learning communities are a well-known context for healing, both psychologically (Kornarakis 1991) and psychiatrically (Tsegos 2012), also for the psychological recovery of children (Farwell and Cole 2001). Extending this context on the Internet could generate a very interesting and promising healing framework.

The research carried out by Swan (2002) concludes that there are three factors associated with the perceptions of satisfaction and learning of the students who participate in virtual learning communities: interaction with the course content, interaction with the course instructors and interaction between the participants of the course The findings suggest some verbal immediacy behaviors that can support interaction between course participants. Support for student interactions with content, instructors and, in particular, among them.

The results of the research carried out by Duncan, and Barber-Freeman, (2008) give us that students in the learning community obtained higher grades, improved their writing skills, increased their communication skills and felt a closer bond between Yes when they worked together to achieve the common objectives of the course. Possibly the most important benefit that students in learning communities receive is a sense of achievement and the establishment of lifelong friendships that were formed with other students. The key to learning communities using cohort development is shared experiences.

These results are reinforced by the conclusions of Keengwe and Kang, (2013) in which the design and effective development of virtual learning communities and combined courses depend on a deep understanding of the history, current activities and beliefs of students. participants.

Applied to organizations for Homan and Macpherson (2005) the significant development and implementation of e-learning in this case, companies suggest that there is a shift towards the third generation of corporate universities, supported in virtual learning communities has the potential to be A strategic learning tool, but like other technologies, is shaped by the contexts in which it is adopted, and has the potential to contribute to the key learning threads.

Finally, Tomkin et.al (2019) states that they found that virtual learning educational communities are strongly associated with active learning and instructors were also more effective than other instructors.

CONCLUSION

Learning communities take a variety of forms, however, all learning communities represent an intentional restructuring of the time and space of collaborators to foster connections between work, training and collaborative work with other collaborators, partners, leaders and teachers.

Learning communities are of great interest now because they are compatible with changing epistemologies about the nature of knowledge, because research generally supports their educational benefits and because they help higher education institutions to fulfill their educational missions and organizations of permanently train their collaborators and both forming for lives of work and service.

Learning communities can be designed to include business staff, since it is a group of people who learn together, the intention would be for both trainers and business staff to learn from the interaction.

A learning community must have a specific intention and a set of structures and strategies that focus the group on that intention. Members should meet regularly, work to create a sense of belonging and maintain their focus on the intention of the learning community, therefore, a learning community is characterized by deliberate structures and strategies and with a purpose that capitalize on the social and social nature. natural of human beings towards a greater objective.

Organizations can incorporate the learning community model to increase understanding and communication, improve problem-solving capabilities and develop an organizational change process to collectively build community.

Learning communities focus on the human element of communities, and the benefits that accrue from the synergies of people in common places or with common interests as they work to share understandings, skills and knowledge for shared purposes.

The concept of learning communities is based on a broad body of theory related to education, administration, psychology and sociology. Learning communities are ideal in an increasingly complex world in which we cannot expect a single person to have sufficient knowledge and skills to face the complexities of institutions, our society and the individuals and tasks to which they are face.

Building learning communities is not easy, it requires a number of subtle and more open processes with influences, both internal and external in organizations, that can facilitate or strongly inhibit the process.

Virtual learning communities offer many advantages to their members: participation (regardless of distance or time) and the ability to participate even for people with disabilities.

REFERENCES

Please refer to articles in Spanish Bibliography.

BIBLIOGRAPHCIAL ABSTRACT

Please refer to articles Spanish Biographical abstract.