Tourism Development Cycle: Doxey Irritability Index

Note. Source: Kozaryn and Strzelecka (2016).

Tourism development planning as a community industry

(*)María Cristina Sosa

(*)Investigadora independiente

Wanda, Misiones, Argentina

macrisol@gmail.com

Reception date: 03/21/2022 – Approval date: 04/21/2022

DOI: https://doi.org/10.36995/j.visiondefuturo.2023.27.01.002.en

ABSTRACT

Tourism has been one of the fastest growing sectors of economic activity before the pandemic; its sustained growth over the years has been due, among other things, to its relationship with the promotion of local economies in less developed regions. But one of the biggest challenges facing development is to improve people's living conditions in a balanced and equitable manner, and this challenge is transferred to the starting point of tourism development: its planning. Tourism development planning has evolved through different approaches, in which interest was focused on certain aspects of development that over time proved not to be sufficient to guarantee a balanced and sustainable improvement of the destination, directly affecting the well-being of local residents and their compliance with the activity. The most current approach to planning is the one that focuses on involving local actors to decide on the tourism development they want in their community. This article reviews the theoretical foundations of this thought, which has a strong base in English literature, but has also been greatly reinforced from the Latin American perspective. It is concluded that tourism planning based on interests and community dynamic, which increases the perception of collective benefits, is key to the sustainability and competitiveness of the tourist destination.

KEY WORDS: planning, tourism development, community participation, sustainability, competitiveness.

INTRODUCTION

The planning of tourism development is an activity that has gone through various facets, characterized at certain times by placing greater emphasis on the economic and physical aspects of the territory, which over time proved to be insufficient to ensure a balanced and sustainable development. As lifestyles evolve, so does the environment and the need to maintain a more balanced relationship between the economic, natural and social capital of geographic spaces is accentuated; this relationship constitutes the main challenge of sustainability, since a development path that leads to the reduction of the natural, cultural and social heritage is no longer sustainable, even if other forms of capital increase (Gallopín, 2003; Dwyer, 2005).

The conception of tourism as an industry is a fact on which there is no generalized position among analysts and, although the word "industry" is commonly used when referring to the tourism sector, it is argued that this meaning is not correct, since there is nothing that could be identified as the "tourism factory”, nor a process of transformation of resources that results in a final or intermediate product called tourism (Boullon, 2006). However, and without pretending to enter into such a debate, this article uses the expression community industry to refer to tourism activity in a figurative sense, in order to highlight the systemic and integrative character that it manages to have in the community by being able to articulate all sectors of it, thus achieving, as a whole, to shape the visitor's tourist experience.

In addition, the adoption of the expressions community industry and tourism industry, seeks to highlight the importance of the activity for local development, which puts it on a par with other sectors of economic activity such as agriculture, construction or the industrial sector itself. After all, before the pandemic, tourism had reflected a sustained expansion over the years, with a great contribution to the global economy and even exceeding, in percentage growth, the percentage increase of the world GDP (WTO, 2020).

It must be understood, then, that the planning of an activity of this nature cannot be conceived from a limited point of view, it is a duty to do it with an integral approach, which encompasses all the dimensions of community life. And who can better understand their reality of life and associated problems, if not the community itself that suffers from it? For this reason, the concept of community participation has been placed at the center of the sustainability debate (Taylor, 1995), warning that the voices of those who live and coexist in a territory, local residents, should be the first to be considered when elaborating a tourism development plan; not only because they are directly affected by the actions to be undertaken in the destination, but also because their well-being and support for tourism activity, reflected in the warmth of welcoming visitors, becomes an element of competitiveness (Murphy, 1985).

This article reviews the theoretical underpinnings of this thinking in order to better understand why community participation in tourism development planning has become a key factor in the sustainability and competitiveness of tourism destinations, and what challenges this approach poses to future research on tourism planning.

DEVELOPMENT

Tourism development planning

Planning theory is derived from management theory, where planning is understood as the first of four functions that make up the administrative process, namely: Planning, Organization, Management and Control (see Stoner, Freeman and Gilbert, 1996).

Management theory is a twentieth-century academic discipline that has evolved into several sub-fields of specialization, where time and key historical facts gave rise to various schools and theoretical approaches that would guide thinking about organizations and their management. According to Stoner, Freeman and Gilbert (1996), its beginnings were associated with the need to increase productivity and efficiency, which led to the development of the Scientific Management School in the period from 1890 to 1940. After World War II the emphasis shifted to the complexity of large corporations, and evolved into the Classical Organization Theory School, within which the Behavioral School and Management Science subfields emerged, as organizations began to focus more on human relations and technical management. As business functions became more complex, the Systems Approach and Contingency Approach began to be advocated, emphasizing the interrelational nature and cross-cultural influence of business.

Finally, the most current approach to management theory is the so-called Dynamic Commitment Approach, where "human relations and times are forcing managers to reconsider traditional approaches due to the speed and constancy of change" (Stoner, Freeman and Gilbert, 1996: 53). Although the planning is located at the beginning of the administrative process, the specialization of its field of study and its importance for the normal development of the other management functions, which through the continuous exchange of information allow rethinking the strategies and actions of the plan in order to adapt to changes in the environment, are highlighted (Murphy and Murphy, 2004).

As far as tourism is concerned, the planning of tourism development is relatively recent, the first important works appeared in the 70s with authors such as Gunn, Getz and Inskeep (Gunn and Var, 2002) and, as happened with administrative theory, there has also been an evolution in the theory of planning applied to tourism. Initially, interest was focused on the economic aspects, and later, for a long time, the interest in the physical aspects of the destination prevailed, with the interesting contributions, in the Latin American case, of Roberto Boullon. More recently, the social, cultural and environmental impact dimensions had been incorporated. Among the various planning approaches that emerged along this path are: Developmentalist approach, Economic approach, Strategic approach, Spatial or physical approach, Economic policy approach, Urbanistic approach and Community or regional approach; each of them with an emphasis on certain planning elements, but at the same time with limitations to promote sustainable tourism development (Blanco, 2019).

This evolution in the planning approach, as well as the understanding of the importance of this activity for tourism development, is related to the evolution of the complexity of the tourism industry and to the conception of the tourism phenomenon as such, which is currently characterized by two key elements: the recognition of its wide interrelation with other dimensions of human activity and the awareness of its impacts on the environment (Murphy, 1985; Gunn and Var, 2002).

Thus, while prior to the COVID 19 pandemic tourism continued to consolidate itself as one of the largest industries in the world, at the forefront of discussions about its impacts, scholars have turned their attention to the reduced effectiveness of planning and the need to develop a more holistic, integrated, flexible and responsive coordination scheme that contributes to the well-being of communities (Murphy, 1985; Gunn and Var, 2002; Tosun, 2006).

The ineffectiveness of centralized tourism development plans, driven by government or private initiatives, has been criticized on the grounds that they are often too rigid, inflexible and unrealistic (Murphy, 1985). Commonly, the result of these plans has been the displacement of the control of the communities over their own territories and an unbalanced development of the destination, where important tourist poles are located on the one hand and, on the other hand, less developed sectors or neighborhoods within the same destination, which do not access to the same services and benefits, generating hostilities, conflicts and even rejection from local residents towards tourism managers and visitors (Reed, 1997).

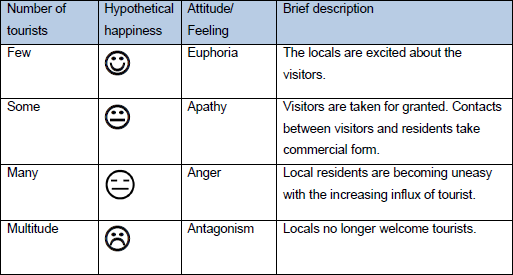

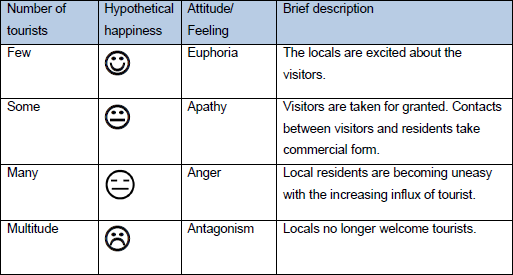

Given that tourism is an essentially relational and experiential activity, the behavior of the host community in the destination plays a very important role, and if planning and development are not adjusted to local aspirations and capacities, community resistance and hostility can lead to raising the cost of doing business or even destroying the potential of the tourism industry in the destination (Murphy, 1985; Cordero, 2009). The Doxey model (Table 1) constitutes a tool through which to understand the importance and linkage between local attitudes and tourism development.

According to Doxey, local residents go through several stages of attitudes, which, it can be argued, correspond to decreasing happiness (Kozaryn and Strzelecka, 2016).

Table 1

Tourism Development Cycle: Doxey Irritability Index

Note. Source: Kozaryn and Strzelecka (2016).

Murphy (1985) suggests that the problem of declining happiness in local hosts can be overcome through a more balanced approach to tourism development planning and management, with greater emphasis on its interrelational nature and a greater balance in decision-making processes among those who hold the funds (governments, big businesses, banks) and those who have to live with the results and alter their ways of life, from whom hospitality is also expected towards visitors. Thus, his proposal focuses on giving locals greater involvement in the stages of tourism planning in the destinations, in order to achieve a more responsible association. Healey (1997) argues that more inclusive planning would help improve the quality of life of many communities, to add material value not only to local businesses, but to those who share the experience of living there, and of working to sustain the critical capacity of a place's biosphere.

These arguments are based on a growing awareness of the dependence of the tourism industry on the responsibility of the host community (Cordero, 2009), so its planning and development is conceived as a "community industry", which must be developed in harmony with the capacity and aspirations of the destination area (Murphy, 1985) and with a view to its long-term sustainability.

Purpose, Concept, Objectives and Planning Scales

The importance of planning lies in the fact that it allows to anticipate and regulate changes in the destination, in order to promote a more orderly and sustainable development, while the lack of planning procedures can guide the generation of irreversible social, cultural, economic and ecological impacts of tourism (Cordero, 2009). For D'Amore (1992), in the report "Our Common Future" of 1987 the World Commission on Environment and Development expressed with a high level of optimism that the problems of development and the environment could be solved if planning were able to link these two spheres.

The purpose of planning is to create action plans for a foreseeable future and implement such actions (Gunn and Var, 2002). To achieve this, planning acts as a process, linking decisions and actions designed to lead to a single objective or a balance between several goals and objectives (Hall, 2008; Murphy, 1985). In this way, planning can be defined very simply as "a process of human thought and action based on that thought". It involves decision-making and policy-making, but dealing with a set of interdependent and systematically related decisions rather than individual decisions (Hall, 2008: 8).

Murphy (1985) pointed that in the laissez-faire atmosphere of western societies, where the tourism industry has been dominated by the business sector, most of the objectives have been oriented towards economic growth and commercial interests, where tourism has been used as an agent of economic development in depressed peripheral regions and as an export activity; but this form of planning is no longer acceptable, due to the fragility of certain environmental resources and the need to protect them if a long-term tourism industry is to be developed. Additionally, McCool (2009) points out that in constructing sustainable tourism goals, the rational planning approach has traditionally been followed, which marginalizes experiential knowledge and privileges the scientific elite, often excluding those who are affected by decisions.

Encompassing the objectives of tourism development within a community framework allows some local control and direction to be above the emphasis on business. In this regard, McIntosh (cited by Murphy, 1985) proposed four key objectives:

And from a more current perspective, Gunn and Var (2002) suggested for better tourism development the following four key goals: 1. Increase in visitor satisfaction, 2. Improvement of the economy and business success, 3. Sustainable use of resources, 4. Integration of the area and the community. Thus, the involvement of the community in tourism planning and management has been addressed by several researchers (Haywood, 1988; Reed, 1997; Reid, Mair and George, 2004; Mbaiwa and Stronza, 2010; Lima and d'Hauteserre, 2011; Nault and Stapleton, 2011; Fiorello and Bo, 2012; Fox-Rogers and Murphy, 2013; Jaafar, Rasoolimanesh and Ismail, 2015; Tolkach and King, 2015; Bodosca and Diaconescu, 2015; Hatipoglu, Alvarez and Ertuna, 2016, Ruiz, 2017).

It is remarkable the model of tourism planning for local participation that Murphy (1985) suggested early and which he called "ecological approach", fitting tourism within an ecosystem in which visitors interact with the living (hosts, flora, fauna, services) and non-living (landscape, sun, sea) parts of the ecological system that characterizes the community, to consume a tourist product. There is interdependence in the system: the natural resources and the community need the tourism industry to inform, transport and accommodate visitors, while in the process they obtain tangible benefits (such as income and services, for example); and in turn, the tourism industry needs the resources, which are the basis of the activity, and the support of the destination community to fulfill the function of hospitality (Murphy, 1985).

Based on this conception, the same work identifies three scales of planning, associated with different objectives, according to the predominant interests. At the national scale, the main concern is focused on economic and social issues, so tourism objectives at this level are mainly manifested through policy statements aimed at the development and conservation of resources that will improve the national tourist attraction and depressed regions in particular. At the regional scale the main concern is the capacity of the environment and the loading route, given regional constraints; objectives become more specific, employing ecological models and systems to determine the relevance of compensation and consequences. On the local scale, the implications of physical development and the wishes of residents are more important. Local issues include concern about the impact of development proposals on the site and their effect on the community, which essentially relate to local physical and social carrying capacity, but in addition to this, concerning the economic return that can be expected from the industry and consideration of the public, in which proposals will produce net improvements compared to existing conditions, so at this level broad participation in the decision-making process is recognized as a legal and practical necessity (Murphy, 1985).

Gunn and Var (2002) identify the local scale as the destination scale, defining the latter very simply as the "community and its surrounding area". They warn that communities play a key role in tourism and that often the growth and rapid expansion of mass tourism have impacted them beyond their capacity to accept tourists: "Destination areas must be planned with sensitivity to social, environmental and economic impacts. (...) participatory planning is essential. Residents deserve to know how tourism development will affect them" (p. 26).

Community orientation can be seen in the policies and objectives of current tourism development plans. In Canada, for example, the promotion of tourism based on small communities with natural resources, led to the development of acceptable guidelines for its future expansion, which have been based on codes of ethics and guidelines for the Canadian tourism industry, in order to guide its policies, plans, decisions and actions. These guidelines recognize that the sustainability of tourism depends not only on the delivery of a high-quality product, but also on a continuous spirit of welcome within the host community (D´Amore, 1992).

Community, Common Good and Community Participation

Healey (1997) expresses that sometimes the word community is used simply as a synonym for "the people living in an area", highlighting the geographical connotation of the concept, but that it is also usually linked to a deeper meaning: firstly, the image of an integrated social world based on place and, secondly, has connotations of opposition to business and government (Williams and Mayo, cited by Healey, 1997).

In the first case, the image of community is based on a geographically limited space, where life, work, family and Friends relationships take place, where people live in interconnected social networks and share a moral order, a culture of common values, systems of meaning and ways of doing things (Cohen, 1985), that is, a vision of community that integrates the geographical aspect with the cultural aspect (Cordero, 2009), where people may be different, both individually and in their resources and opportunities, but reside in a common habitat and maintain a common moral and perceptual scheme.

The second case, following Healey (1997), involves an image of the community as an opposition to the dominant force. It speaks of community versus the state or corporations, or the forces of capital; it expresses the shared interest as human beings in trying to live their lives, versus the sphere of business organizations and political institutions. However, those who mobilize in these two spheres also belong to the community and have common concerns about daily life, so they must manage the relationship between formal work and other dimensions of life.

Therefore, the aforementioned author proposes not to separate daily life, private, from the formal and public sphere, but rather, to reinterpret the concept of community to recognize not only the integrated nature of living, working, reproducing and relating in a context, but also the difficulty of carrying out this integration, referring to the practical organization of everyday life with representations in formal settings, where the community can find expression and organize collective activities. This approach represents a point of view that challenges the separation of work and governance, recognizes social diversity and that people, although different, faced with the challenge of carrying out daily life can seek a public sphere where they can collaborate with neighbors to alleviate obstacles, discuss issues of common interest and combine with others who care to do something about it. In this sense, the community should be understood as a "living organism" (Tönnies, cited by Álvaro, 2010) and as such, an entity of complex organization where relationship, interaction and exchange are present in all orders that affect the structure of life.

A clear example of this can be found in Floreana, in the Galapagos Islands, a small territory where despite the diversity of origin of its inhabitants and its consequent lack of homogeneity and socio-cultural identity, families were able to join in collaboration to manage locally the tourist activity, which for a long time had been exploited by external agencies that sent their cruises to the island to enjoy its paradisiacal landscape, without this having an impact on a benefit for the inhabitants of that territory. Bringing families together for a common purpose and the implementation of their self-organization capacities to control to some extent the tourist activity, facing the overwhelming market and the state, without resisting them, but seeking to install an alternative tourism model such as community tourism, led them through a process that, in itself, meant building community. In relation to this experience (Ruíz, 2017) concludes the following:

It is not, therefore, a question of "breaking with the world", nor of proposing exclusionary alternatives that collide with their own ambivalent interests; but, rather, it is a question of generating complementarities without directly questioning the hegemony of the State and the market, but whose implementation can undermine it.

There is no need for social homogeneity or indigenous ancestry to build community; new commons can be created beyond the anchorage to history or "traditional" activities. The common and the community are matter –above all- of will and rationality (p.352).

Linked to the concept of community is that of the "common good", which arises as a product of life in common. Álvaro (2010) points out that the term community expresses reciprocal relationships that tend towards unity, or more precisely to union, so that, without relationship and without union, life in common is not conceivable. St. Thomas Aquino conceived the common good as the good of all, while Machiavelli conceived it as the good of the state (Sehringer, 2010); without pretending to enter into the philosophical debates of this expression, what is highlighted here is that the common good is that shared by many, being a group, community or society, and as such requires an availability and management of use that is neither limiting nor excluding, but also, that is sustainable, in order to avoid "destructive tragedies", because in Aristotle's thought "what is common to the majority is, in fact, the object of the least care" (Ostrom, 2000: 25-27).

Tourism is based on common goods, since it involves the resources of the biosphere. Sustainable tourism recognizes that the local community is affected by tourism development and seeks to give it an effective voice in decisions about forms of tourism that can be adjusted to its environment. Among the costs of tourism for the community can be noted the intrusion, congestion, rising prices, population growth, pollution, increase in social inequality, prostitution and crime, among others (Taylor, 1995; Ap, 1990).

Studies conducted to assess community perceptions reveal that there are differences in the acceptance of tourism development among dependig on whether they are local residents, companies, government, tourism entrepreneurs who are within the community but who are not part of it, etc. Madrigal (cited by Taylor, 1995) demonstrates that length of residence and native status are important factors in shaping residents' perception of tourism development; in this regard, the findings of Lankford and Howard (1994: 134) suggest that "if residents, even long-term natives, feel that they can exert some control over the development process, much of their fear regarding the development of tourism may be reduced", while other studies reveal that those who benefit from tourism observe less its negative impacts compared to other residents (Jamal and Getz, 1995).

Therefore, sustainable tourism also seeks to ensure a reasonable distribution of the income and benefits derived from tourism activity to the local community, in order to promote a balanced improvement in the quality of life of the locals, their support and collaboration with the sector. An example that was already mentioned above is Canada, where the initiative to minimize the impacts of tourism has been channeled through normative instruments: the code of ethics for the tourist is based on the recognition that a high quality in the tourism experience and its long-term sustainability depend on the conservation of natural resources, the protection of the environment and the preservation of cultural heritage; while the code of ethics for the tourism industry adds to the quality of the product, the continuous spirit of welcome of the employees and the host community (D ́Amore, 1992: 261-262).

Analyzing Murphy's arguments, Taylor points out that the recognition that destination residents are at the core of the tourism product gives a double meaning to the idea of participation: the desires and traditions of the local population should shape tourism development, firstly, because they are part of the overall attraction of the community and also, because they should act as hosts, whether or not they are directly involved with the sector. The "warmth of welcome" is used in the promotion of what is often considered a key asset of the community, given that a friendly community represents an attraction for all types of investment and a valuable element for the publicity of the tourist destination (Murphy: 1985; Taylor,1995; Fiorello and Bo, 2012).

According to Taylor (1995), since the publication of Murphy's work, Tourism: A community aproach, the concept of community participation has been placed at the center of the sustainability debate, and in this sense, its incorporation among the objectives of tourism development has led to a series of questions, in which scholars on the subject have made contributions that help clarify the type of participation that leads to sustainability, understanding that there are different forms of participation and that not all of them imply an active involvement in decision-making, leading this to different results in the level of benefits perceived by the community (Sosa and Brenner, 2021). But the latter is a discussion beyond the scope of this article.

What is clear in this brief analysis is the need to think of tourism development as a community industry that connects all sectors of the local territory, and as such, is based on the voice and interests of local actors that operate in each of these sectors, promoting dialogue and weaving collaboration networks that allow the enhancement of collective well-being and support for tourism activity, as key elements for the good development and image of the destination. Haywood (1988, cited by Leiva, 2022) illustrates this as follows:

The host community is the destination where individual, business and government goals become tangible products and images of the industry. A destination community provides the community assets (landscape and heritage), public assets (parks, museums and institutions) and hospitality (government promotion and welcoming smiles), which are the backbone of the [tourism] industry (p. 195).

Additionally, Jamal and Getz (1995) emphasize that the aetsss and resources of a destination community such as its infrastructure, recreational facilities, natural and cultural attractions, etc., are shared by numerous actors of the local destination (inhabitants, visitors, public and private sector interests such as external developers, financiers, entrepreneurs), noting that "tourism development acquires the characteristics of a public and social good [so] none organization or individual can exercise direct control over the destination development process" (p.193).

The recent health crisis unleashed by Covid-19, which profoundly impacted the tourism industry as a result of the complete paralysis of activities, showed us even more the importance of not depending on external programs and policies to boost local destinations and economies, but rather strengthening communities so that, similar to a factory with systematized processes, its production and dynamics are not paralyzed in the face of the threats imposed by globalization. A clear example of this is seen in the Chinese city of Whuhan, a place linked to the beginning of the pandemic, where one of the strategies that allowed its rapid recovery, unlike many Western countries, was the promotion of domestic tourism as a reactivation policy for all sectors in the Eastern territory. Therefore, Leiva (2022) expresses the following:

In the current context of climate and health crisis, in which the vulnerability of tourism has been clearly shown, community-based planning should focus on strengthening the internal capacities of local communities, the diversity of their economies and the prevention of adverse events, rather than on the economic growth of the tourism industry, even if it arises from participatory and community processes (p. 203).

To conclude this reflection, it is pertinent to highlight an observation by Murphy (1985) that continues to be applicable to the present date, and that is that although the approach to planning in tourism has changed, it is still far from achieving a balance between environmental and social priorities along with economic ones; "the emphasis on community responsibility must continue, since this industry uses the community as a resource, sells it as a product and, in the process affects the lives of all" (p. 185).

Achieving sustainable tourism development depends, more than ever, on involving the community in the search for solutions, since it is the direct recipient of the problems caused by inadequate development. Aguirre (2007: 13) affirms "sustainable tourism will never be achieved by decree, but by participation". Acording to the author, sustainable tourism continues to be a "magical concept", of which much has been said and discussed, but there are still thousands of cases in Latin America, and other latitudes, where things are not done as they should be, and it is time to channel reality in a pragmatic way towards what is so longed for.

Although in terms of public management this represents a challenge, the possibilities that are currently generated through the development of ICTs, make its execution highly feasible; and what really remains to be overcome, echoing the words of Boullon (2006: 6), is the fulfillment of a single condition: "that one wants to do and has the necessary time to accomplish a task that requires the rescue of part of the energy used, until today, in growing for the sake of growing; for trying to grow with development, that is, to grow well".

CONCLUSION

The review and theoretical analysis presented in this document allows us to understand the importance of tourism development planning and how its approach has evolved to incorporate community participation as a key element to guarantee a balanced and sustainable development, but also to become an element of competitiveness of the destination. It can be seen that the foundations on which the first authors were based in incorporating the community approach to tourism planning and management have not lost validity, but on the contrary, has been reinforced through experiences and studies conducted in a great diversity of countries, which under very different cultural, political, social and geographical contexts, reveal the same need: to turn tourism into an engine for the healthy development of the territory, considering the interests, desires and priorities of those who inhabit it.

Tourism activity is based on common goods, and as such, it must be ensured that the benefits derived from it reach as many residents of the community as possible, whether or not they are directly involved in its provision, so its planning must consider, in addition to physical and economic factors such as the generation of foreign exchange or employment, those social and cultural aspects that affect the quality of life of people, keeping them happy and predisposed to a healthy exchange with visitors.

The inhabitants of the community should not perceive tourism as a threat to their way of life, but rather see it as a way to improve the conditions of development of the territory, maintaining an adequate balance between the expansion of tourism and the development of other activities, such as agriculture, livestock, fishing or production. Conceiving tourism development planning as a community industry implies weaving collaboration networks among all the economic sectors present within a territory and increasing the perception of collective benefits, so that each local actor, from the place where he/she operates, and when it comes into contact with a visitor, becomes a good host for him/her.

Likewise, in all tourism planning, the natural heritage must be carefully protected in order to avoid the destructive tragedies that usually weigh on it when, being in common use, it does not receive the necessary care for its preservation; but at the same time, it must be avoided that, in order to preserve the natural resource, the control of the same remains under the orbit of a single actor, public or private, that does not contemplate among its decisions the generation of benefits for the whole community.

There is no doubt that the planning of tourist destinations is a complex task; on the one hand, because of the interdependence that exists between so many stakeholders, and, on the other hand, because of the fragmented control that usually exists over the resources of a destination, which makes the task of integrative planning difficult. However, the need to develop competitive yet sustainable destinations leads us to face this challenge by seeking different strategies to bring together the voice and will of as many local actors as possible. At times, there will not be full certainty of the success of the strategies to be implemented, but the search also involves a process of trial and error that help to perfect the techniques and actions of the future.

As can be seen, much remains to be discovered in this field of research and, above all, to carry out different forms of approach to community realities and practices that help develop methodologies and mechanisms that facilitate local involvement, to replace the highly institutionalized participation schemes or mechanisms that have taken place so far, generating criticism of its lack of flexibility and effectiveness (Blanco, 2019). The impulse that is being seen in the methodology of participatory action research that has its origin in Latin American territory, and is rapidly expanding to other regions within the field of scientific research, seems to mark a path where it is expected that future research will reinforce attention to these aspects, and that they will allow discovering effective forms of participation in the planning of tourism development.

REFERENCES

Please refer to articles in Spanish Bibliography.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Please refer to articles Spanish Biographical abstract.